From time to time I am asked to explain Public Health to students, colleagues from other disciplines or a more general audience. A traditional approach might be to structure such a session around the three domains of Public Health (health improvement, health protection, quality improvement), building on specific examples:

- Tackling cholera in the Victorian era: John Snow and the Broad Street Pump

- Understanding and reducing health inequalities from the Whitehall Study (1967), Black Report (1980) Whitehall II study (1985) to Fair Society Healthy Lives (2010) and beyond

- Maslow’s hierarchy of need and Dahlgren and Whitehead’s models that summarise the importance of social determinants of health

- Epidemiological studies and the progression through descriptive studies to observational and experimental studies, using Richard Doll and Bradford Hill’s studies on smoking. Doll and Bradford Hill observed a rise in lung cancer cases, then explored potential causes via a case control study with lung cancer patients vs other patients (published 1950), then a cohort study with doctors who smoked or didn’t smoke (1954).(+) It took a further 51 years for the Smoking, Health and Social Care (Scotland) Act (2005) legislation banning smoking in public places and the ban on smoking in cars with children a decade later.

((+) For an excellent clear description of different types of epidemiology studies see Beaglehole et al’s Basic Epidemiology (free download in multiple languages)).

However, this approach perhaps doesn’t highlight the distinction between individual and population health clearly enough for a general audience. After all, one response to the final example above is to talk about uptake of smoking cessation services and other individual approaches to health. A GP may respond that Maslow’s hierarchy applies to an individual as well as a population – a patient is unlikely to be receptive to ideas about health screening or treatment if they are hungry or worried about their home or job.

As I prepare for a session teaching 4th year medical students this week I am keen to try something different, though informed by these and other key Public Health topics. The focus here is on highlighting the differences between approaches to improve individual and population health.

There is a lot of interest to Public Health in the scientific and general press at the moment. For example, over the last few weeks there have been major studies/ stories about the following topics in the world’s top medical journals:

- Air Pollution and Climate Change: Lancet study using data from the Global Burden of Diseases study 2015; BMJ editorial on the role of doctors in the US in Trump/ post-truth era

- Alcohol: Lancet review of alcohol control policies in England, including Minimum Unit Pricing. The paper notes “striking contrast” between alcohol-related mortality in England (increasing) and liver disease in much of the rest of England (decreasing). Understanding variation is an important part of Public Health work, as we shall explore.

- HIV infection: Persisting impact on Public Health in Muirhouse, Edinburgh

- Ebola: Interplay between virology, genetics and Public Health in understanding and ultimately controlling 2013-16 outbreak

- Sugar, salt and self regulation: Editorial in the BMJ

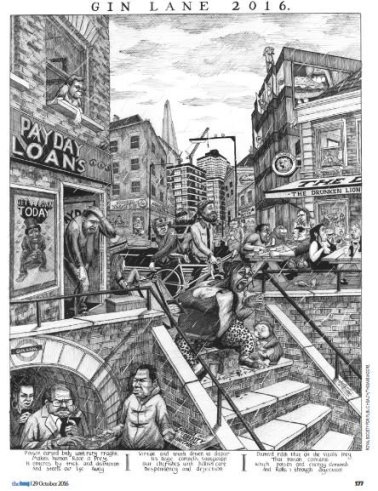

We can learn from commentary around these stubbornly persistent threats to health: eg this individual reflection on diesel fumes and health in the Guardian. Individual response and action is important, and there is clearly a role for behaviour change and medical treatment, but measures to reduce the impact of these global threats to human health will take work at all levels, from individual to supranational and global approaches. In a period of political and economic uncertainty Public Health tools at regional, national and international level (tax, cost, regulation, legislation) are being discussed again, around topics that would have been as familiar Hogarth as to our Public Health predecessors in the Victorian era and first half of the 20th century.

(Image from BMJ 29 October 2016)

Public Health’s influence comes in cycles: it is perhaps no surprise that there is discussion around regulation, legislation and evidence in response to a US President supportive of anti-vaxxers and climate change deniers and Brexit negotiations threatening supranational cooperation and legislation (eg see news story on European Medicines Agency in London).

We already know the big non-communicable disease threats to health. The question becomes less “what do we know?” and more “what can be done?” to improve population health. It is all too easy to say that we do our bit as individual professionals (eg by cycling rather than taking the car to work), or to focus specifically on individual patients in our work (eg in working out how to reduce obstacles to care, or promote uptake of evidence based approaches). These are tangible, achievable steps, reinforced by the endorphins from the ride, the surge of serotonin in achieving another goal, the satisfaction of another person helped. It is much more difficult to achieve whole system successes, overcome legislative hurdles, navigate uncertainties or limitations in evidence at population level (vs traditional randomised controlled trials). Nonetheless, we can learn from our own experiences, and those of others, in identifying areas for improvement and obstacles to change at a population level.

(Image: Obstacles to cycling in south east Edinburgh, plus contrast between built and natural environment, taken on morning of 14 April 2017).

The tools that we can deploy in planning and influencing change at a population level are among the first to be taught to Public Health specialists during their training, but it is worth revisiting and reflecting on lessons learnt in the intervening period. I have added in one framework that will be less familiar.

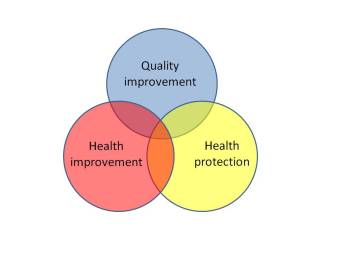

The three domains of Public Health

- Health improvement is not just about health literacy, education and behaviour change – it is also about the social determinants of health (eg housing, employment), and legislation, regulation and cost/ tax measures

- Health protection is not just about traditional communicable disease work (focusing on managing cases and their contacts) – it also relates to environmental health (eg water, air), climate change, road traffic accidents and more. Again, this extends to cost, tax, regulation and legislation

- Quality improvement* is well encapsulated in 6 words: think big, start small, test fast (adapting a Mayo Clinic Center for Innovation tagline). It often starts at an individual level, with small level testing (eg changes to the phrasing of a question for successive patients), but with a much more ambitious aim in its sights.

(*This domain is more traditionally referred to as “health and care service improvement”, but I would argue that this potentially limits the scope of Public Health work.) The three domain model used to be described in full on the FPH website. I don’t think that’s available anymore, but there is a good description by John Middleton here.

Bringing the three domains together (the Reuleaux triangle at the centre of the domains), the most commonly cited examples are screening and immunisation: both require a whole system approach; both require continued monitoring, testing and adaptation over time. However, they are rather clinically focused for a more general discussion; topics such as water and air quality could also sit in this central position by taking a slightly wider approach to the third domain.

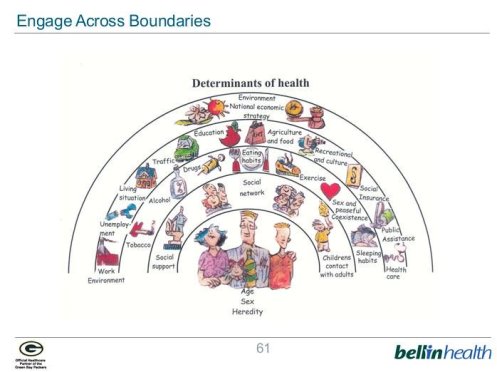

Dahlgren and Whitehead’s determinants of health model has been updated in this figure (via George Kerwin, Bellin Health, presentation, Health Care Improvement Scotland QI Connect webinar 10 Nov 2016).

The main influences on health across a life time are not health service based.

In their widest sense the three domains of Public Health described above require us to think across the levels from individual biology to national economic and environmental factors. While a piece of work focusing on increasing uptake of a maternity benefit may start with a small number of pregnant women, the ultimate aim would be to reduce maternal poverty more generally, bringing our learning to the design and implementation of the benefits and tax credit system.

Though not usually taught as a Public Health topic, the Edwards Deming’s Lens (or system) of Profound Knowledge, well known through Quality Improvement work, provides a useful reminder for the balance of approaches required for success.

These four overlapping areas remind us to look for unnecessary variation (in process or outcome), to build knowledge through testing (rather than just description), to consider human factors (which may relate to patient, clinician, elected member or any other relationship), all the time thinking of the overall system (whether a clinic, ward, or wider economy).

Thinking about smoking and lung cancer, the period between Doll and Bradford Hill’s first observational studies (published 1950 and 1954) and the smoking bans in public places (2006) and in cars with children (2016) reminds us quite how complex and time consuming Public Health progress can be.

We can apply this learning to current risks to health such air pollution (which was in fact a concern of Doll and Bradford Hill back in 1950). With 4.2 million deaths globally in 2015, this is as much of a Public Health crisis as any communicable disease pandemic. As for smoking:

- the evidence around air pollution and health is observational

- there are powerful commercial interests (and politicians) keen to downplay the risks of air pollution (frequently using lessons learned from big tobacco)

- a substantial proportion of the general public (and therefore electorate) is more attached to their car than “invisible” risks to health.

We therefore need to learn from previous Public Health successes, but navigate a faster resolution this time around. Social media provides opportunities, but commercial and political interests have experience and large audiences on these new platforms. Big data and massively expanded computing power should provide more sophisticated analysis than ever before (eg street level data informs Demings “understanding variation”), but the studies will still be observational in design, with the same limitations (biases and confounding factors) as the smoking studies.

See also: advocacy toolkit and a 2 minute film on using the lens of profound knowledge to increase uptake of maternal benefits

Geoffrey Rose is perhaps most famous for his bell shaped curves and the “prevention paradox” (a preventive measure which brings much benefit to the population offers little to each participating individual).

Shifting from treating high risk patients (eg just patients at increased risk of cardiovascular disease) to a universal population-based approach reduces population risk and reduces inequalities (narrows the width of the curve).

Universal approaches that have been suggested in response to Rose’s work include:

- food formulation (reducing sugar, fat) to reduce obesity and cardiovascular disease

- fluoridation of water to improve oral health

- and supplementation of flour or cooking oil with folic acid to reduce incidence of neural tube defects

Self regulation by major commerical interests (eg “Responsibility Deal” promoted by UK coalition government of 2010) has not been shown to be effective for promoting healthy choices around food and alcohol. Universal approaches require cost, tax, regulation and/or legislation to be successful.

Inequalities (both health and income) are a central focus of Public Health work, but are arguably the most resistant to change of all measures.

Michael Marmot’s report Fair Society Healthy Lives (2010) provides a comprehensive summary of health inequalities and actions to tackle them. Concepts introduced in the report, such as “proportionate universalism” and “lifestyle drift”, are central to a Public Health response.

Proportionate universalism is defined as “the resourcing and delivering of universal services at a scale and intensity proportionate to the degree of need”, acting to reduce both the gap between richest and poorest, and across the social gradient.

Lifestyle drift is defined as “the tendency for policy to start off recognizing the need for action on upstream social determinants of health inequalities only to drift downstream to focus largely on individual lifestyle factors”.

It is this last point which is perhaps the most useful single measure of whether we are taking a population approach: examples abound of lifestyle drift in UK policy making – eg this story about covering buggies because of air pollution in London. Obesity strategy is another example, where committees start with discussions about town planning, promoting active travel and reformulating foods, but end up setting targets around completed weight management interventions instead. Public Health work, and actions to reduce inequalities, are difficult.

(Scottish Public Health Observatory reports and online profiles provide a useful summary of small area data and variation in outcomes across Scotland.)

In conclusion, this blog has introduced some Public Health tools which will help frame issues from a population health perspective. The following matrix adapts the Dahlgren and Whitehead determinants of health model to consider interests, influence, evidence, cost and newsworthiness of actions around population health. Take a Public Health topic of interest and use the matrix to formulate your ideas. Post reflections in the comments box below.

Slides for teaching session (version 1) available here.

Dr Graham Mackenzie

Consultant in Public Health

17 April 2017

(Featured image was taken in Leith, near Edinburgh, on morning of 17 April 2017).

Succinct, inspiring and thought provoking as ever Graham! Thank you

LikeLike

Hi Mandy, good to hear from you and thanks for the feedback. Hope all well with you, Graham

LikeLike

Pingback: Some thoughts on digital innovations in Public Health – #ScotPublicHealth

Pingback: What do you actually do then – Sheffield DPH