This is a brief first look at the WAAW / EAAD 2020 campaign week that I prepared shortly after the campaign week ended. I did not share it at the time as other work took priority (clinical work and training commitments during the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic). I have posted it here for interest so that lessons can be learnt for the 2021 campaign

Methods

This summary of WAAW/ EAAD 2020 looks at the 8-day period from noon on Tuesday 17 November to noon on 25 November 2020 (UTC). This period captures tweeting across the full week allowing for international time zones.

Data were collected with TAGS (https://tags.hawksey.info/get-tags/) using the following search strategies. Searches 2 and 3 were run from mid-point in campaign, collecting tweets retrospectively, providing full coverage of the 8-day period (Table 1).

Table 1. Search strategies applied across period noon Tuesday 17 November to noon on 25 November 2020 (UTC)

| Search 1 | Search 2 (added after preliminary examination of search 1 results mid campaign) | Search 3 (plain English terms) |

| #eaad #eaad2020 #eaad20 #waaw #waaw20 #waaw2020 #antibioticresistance #antibioticguardian #keepantibioticsworking #antibioticawareness #worldantimicrobialawarenessweek #worldantibioticawarenessweek #antibioticawarenessweek #stopsuperbugs #aaw2020 #aaw20 #waawafrica #antimicrobialresistance | #stopdrugresistance #NOValenParaTodo #ncasaaw2020 #usaaw20 #beantibioticsaware #youthstewardsofamr #youthagainstamr #antibióticos | “antibiotic resistance” “antibiotic guardian” “keep antibiotics working” “antibiotic awareness” “antimicrobial awareness” “antibiotic awareness” “stop superbugs” “antimicrobial resistance” “stop drug resistance” “be antibiotics aware” “youth stewards for amr” “youth against amr” |

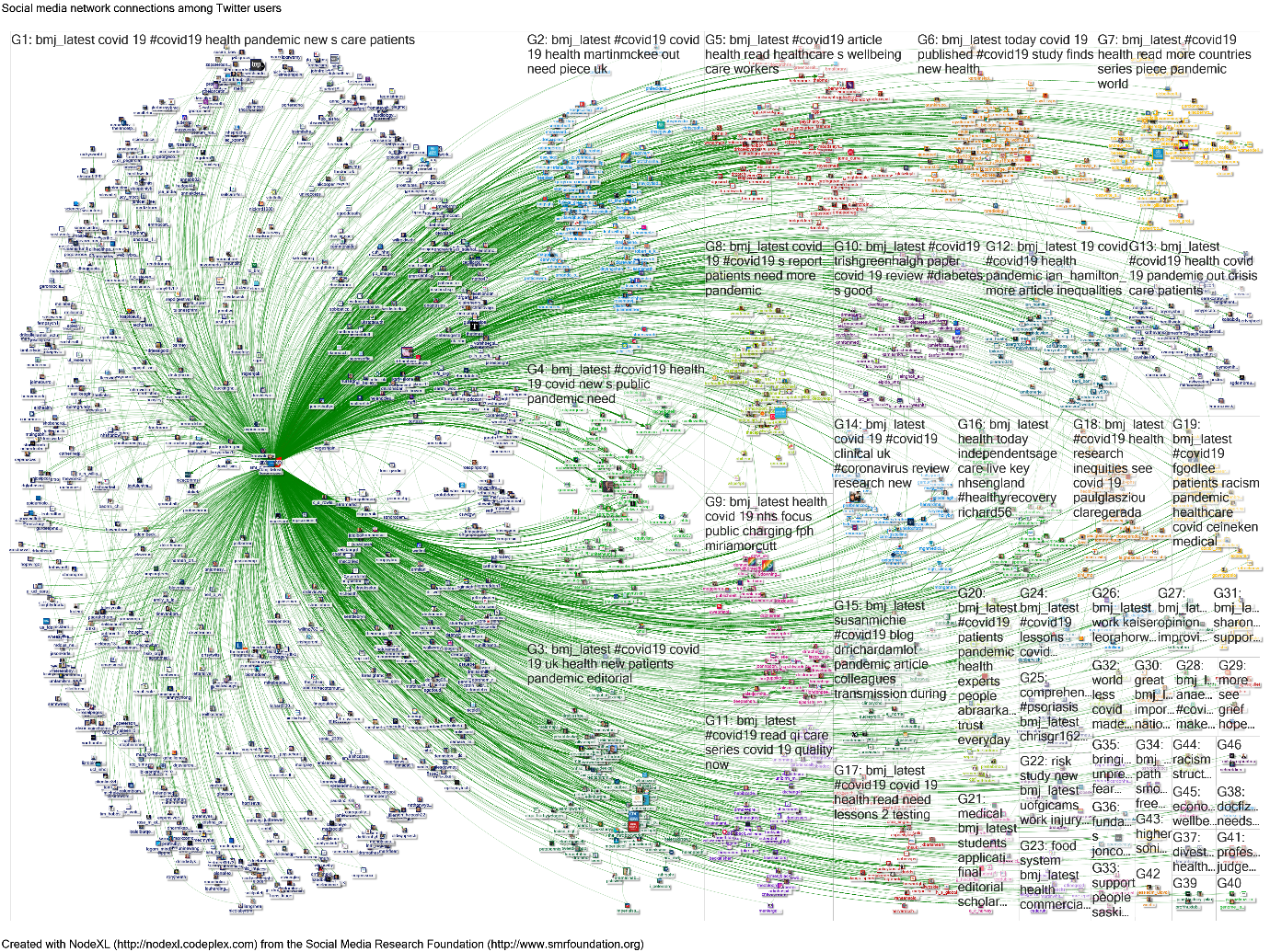

Data were then re-collected using the 19-digit unique tweet identifier in NodeXL, on 27/11/2020. The NodeXL report and map can be viewed here: http://nodexlgraphgallery.org/Pages/Graph.aspx?graphID=242304. Data are available from Graham Mackenzie on request, as the file was too large to upload to the NodeXL Graph Gallery.

NodeXL records information on tweets and retweets, tweeters and retweeters, Twitter accounts mentioned in tweets (either in replies or body of tweet), and hashtags. Further information is available from the 2018 campaign: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0924857920304209, and NodeXL data are available for campaigns since 2016, albeit with different search strategies.[1]

Results

Overall, 6533 tweeters posted 16,361 tweets, receiving 38,817 retweets.

Of these tweeters 628 (9.6%) received 80% of all retweets from their 5,966 tweets, while 3,353 (51.3%) received no retweets from their 4,605 tweets.

Looking just at tweets using #AntibioticGuardian (as per request by a co-author on earlier papers)[2], there were 412 tweeters who posted 986 tweets, receiving 1,731 retweets. Of these, 57 tweeters (13.8%) received 80% of retweets from their 393 tweets while 191 tweeters (46.4%) received no retweets from their 237 tweets.

The top 20 hashtags overall on the basis of retweets are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Top hashtags by number of retweets received

| Hashtag | Number of RTs received | Number of tweets posted |

| #antimicrobialresistance | 11,028 | 3,131 |

| #waaw2020 | 10,583 | 4,134 |

| #amr | 6,371 | 2,519 |

| #waaw | 6,141 | 2,302 |

| #keepantibioticsworking | 4,323 | 1,661 |

| #antibioticresistance | 3,864 | 1,492 |

| #worldantimicrobialawarenessweek | 3,247 | 1,291 |

| #eaad | 2,943 | 764 |

| #antibiotics | 2,701 | 1,076 |

| #africawaaw | 2,603 | 929 |

| #covid19 | 1,893 | 484 |

| #antibioticguardian | 1,731 | 986 |

| #antibióticos | 1,627 | 434 |

| #stopdrugresistance | 1,547 | 187 |

| #worldantibioticawarenessweek | 1,266 | 230 |

| #onehealth | 1,225 | 469 |

| #antibioticawarenessweek | 1,204 | 788 |

| #beantibioticsaware | 1,188 | 869 |

| #usaaw20 | 1,117 | 769 |

| #stopsuperbugs | 875 | 289 |

Source: NodeXL, searches 1-3, noon on Tuesday 17 November to noon on 25 November 2020 (UTC)

Tweets frequently included more than one hashtag as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Number of hashtags used in tweets

Source: NodeXL, searches 1-3, noon on Tuesday 17 November to noon on 25 November 2020 (UTC)

The top 30 tweeters by number of retweets received are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Top 30 tweeters (by retweets (RTs) received)

| Tweeter | RTs received | Tweets posted | % of RTs received | Cumulative % of RTs received | Followers |

| @who | 2,774 | 36 | 7.1% | 7.1% | 8,624,400 |

| @nobelprize | 735 | 3 | 1.9% | 9.0% | 721,134 |

| @cdcgov | 634 | 12 | 1.6% | 10.7% | 3,385,741 |

| @prangob | 614 | 17 | 1.6% | 12.3% | 5,234 |

| @fao | 580 | 11 | 1.5% | 13.7% | 408,836 |

| @ncdcgov | 402 | 24 | 1.0% | 14.8% | 1,161,132 |

| @drdianeashiru | 373 | 79 | 1.0% | 15.7% | 5,918 |

| @oieanimalhealth | 352 | 33 | 0.9% | 16.7% | 20,170 |

| @africacdc | 323 | 44 | 0.8% | 17.5% | 99,989 |

| @kkmputrajaya | 306 | 3 | 0.8% | 18.3% | 1,007,989 |

| @kkeshksa | 295 | 1 | 0.8% | 19.0% | 38,701 |

| @un | 289 | 3 | 0.7% | 19.8% | 13,213,333 |

| @cw_pharmacists | 256 | 45 | 0.7% | 20.4% | 3,294 |

| @whosrilanka | 246 | 30 | 0.6% | 21.1% | 7,563 |

| @drtedros | 246 | 7 | 0.6% | 21.7% | 1,358,519 |

| @tumainimakole | 225 | 86 | 0.6% | 22.3% | 4,116 |

| @compoundchem | 221 | 1 | 0.6% | 22.9% | 84,764 |

| @_facesa | 212 | 67 | 0.5% | 23.4% | 5,997 |

| @unep | 211 | 5 | 0.5% | 23.9% | 1,070,092 |

| @whoafro | 210 | 16 | 0.5% | 24.5% | 219,555 |

| @pfizer | 204 | 9 | 0.5% | 25.0% | 338,370 |

| @bsacandjac | 193 | 21 | 0.5% | 25.5% | 7,192 |

| @eaad_eu | 180 | 27 | 0.5% | 26.0% | 4,120 |

| @spectrummd | 178 | 43 | 0.5% | 26.4% | 444 |

| @phe_uk | 174 | 6 | 0.4% | 26.9% | 426,578 |

| @wellcometrust | 173 | 18 | 0.4% | 27.3% | 187,065 |

| @hselive | 166 | 14 | 0.4% | 27.8% | 160,570 |

| @reactgroup | 165 | 36 | 0.4% | 28.2% | 3,607 |

| @ema_news | 164 | 11 | 0.4% | 28.6% | 53,214 |

| @asoantibiotics | 153 | 21 | 0.4% | 29.0% | 1,687 |

Source: NodeXL, searches 1-3, noon on Tuesday 17 November to noon on 25 November 2020 (UTC)

The top 100 tweets on the basis of retweets received are listed in the following Wakelet summary: https://wakelet.com/wake/KBSc6At7WT-FzECPxweKD (100 tweets posted by 60 Twitter accounts including the following languages: English, Spanish, Japanese, Malay, Arabic and Tamil).

Further analysis of these data –– e.g. the breakdown by tweeter, retweeter and mentioned accounts; multivariable analysis using approach from 2018 campaign (peer reviewed paper here) –– would be possible using the data collected, but would take time.

The main lesson for the 2021 campaign is that we need more hashtag discipline for public health campaigns – hashtag drift dilutes messages, and risks missing otherwise high quality content. Use of additional hashtags can help Twitter users identify content of interest within the large number of tweets posted for a campaign, but that requires careful planning and coordination. Monitoring Twitter activity during such campaigns requires vigilance as new hashtags can emerge during the campaign.

Dr Graham Mackenzie, GP trainee, @gmacscotland 28/11/2020

[1] NodeXL has archived historical reports but I have the data saved. The 2017 data have limitations as NodeXL had not increased character count from 140 to 280 characters at that point – Twitter changed rules early November 2017. The more recent ability to run NodeXL analysis from tweet IDs would allow these data to be re-analysed with full character count.

[2] Excluding tweets that used just #antibioticguardianafrica, #antibioticguardianaward, #antibioticguardianawards, #antibioticguardianawards2020, #antibioticguardians, #antibioticguardianship as these would not be identified using Twitter search for #AntibioticGuardian