NHS Education Scotland provides the following definition:

“Health Improvement describes the work to improve the health and wellbeing of individuals or communities through enabling and encouraging healthy lifestyle choices as well as addressing underlying issues such as poverty, lack of educational opportunities and other such areas.”

Andrew Tannahill provides a more detailed definition:

(Source: Public Heath journal – click image for full article)

Health improvement includes a broader population-based view, including underlying causes (also know as the social determinants of health #SDoH). See #ScotPublicHealth Storify for a more detailed exploration of Health Improvement and Health Promotion.

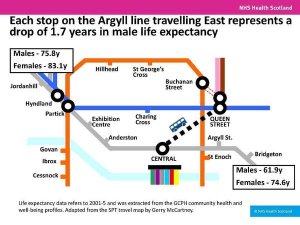

This image, representing drop in life expectancy along the Argyll line in Glasgow, illustrates the importance of #SDoH.

(Click image for link to see rest of Dr Gerry McCartney’s presentation (NHS Health Scotland))

Two commonly cited models, showing how individual and #SDoH interact, are shown below (Evans and Stoddart on left, Dahlgren and Whitehead on right).

Dr. Julian Tudor Hart, GP, famous for the inverse care law, explains more in this video.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs provides another useful framework. First published in 1943 (see #APHCentury Storify) it remains relevant and much cited.

(Click image for link to Wikipedia page on Maslow’s work)

The Marmot Review (2010) identified an important brake on Health Improvement work: “lifestyle drift”. This is

the tendency for policy to start off recognizing the need for action on upstream social determinants of health inequalities only to drift downstream to focus largely on individual lifestyle factors

Read more in article by Jennie Popay, Margaret Whitehead and David Hunter.

The Marmot Review also summarises the concept of “proportionate universalism”, highlighting the importance of the gradient in health outcomes.

To reduce the steepness of the social gradient in health, actions must be universal, but with a scale and intensity that is proportionate to the level of disadvantage. We call this proportionate universalism. Greater intensity of action is likely to be needed for those with greater social and economic disadvantage, but focusing solely on the most disadvantaged will not reduce the health gradient, and will only tackle a small part of the problem.

The #ScotPublicHealth Storify provides a number of examples of health improvement work, and sources of further information from the web and social media.

The NHS Scotland Childsmile programme offers one example of a programme that follows the principles of proportionate universalism. A 2015 paper by Y Anopa et al has shown that the approach has expected savings more than two and a half times the costs of the programme implementation.

The Leith Early Years Collaborative Pioneer Site provides another example of health improvement work, working with low income families to boost their income, but also using the findings to influence national policy and legislation (ongoing). Further information is provided on our quality improvement page. The following video provides a summary from June 2014. An academic paper has been submitted to a journal (December 2015) and is currently undergoing review.

The following table uses Tannahill’s structure for Health Improvement to consider actions to reduce household accidents (NICE Guideline PH30, 2010) and road traffic accidents (NICE Guideline P31, 2010)

For a short overview of health inequalities, see NHS Health Scotland’s leaflet (2015) – click image for full report.

Health Improvement is one the Faculty of Public Health’s 9 areas of Public Health

Graham Mackenzie 30.12.15