Data for improvement can be used to tell a story. A clear narrative illustrates the purpose and flow of improvement work. This scenario has been created to show how easily data can be collected and analysed as part of improvement work. The emojis and simple examples will be suitable for any audience. I tested this out with a group of 50, and it evaluated well.

You can download the animated GIF below.

Imagine you are a factory manager. The factory, which has 90 employees, makes plastic boxes. There are 9 other factories in the company, spread across the world. In addition to the factory workers there are admin and sales and marketing staff.

You receive a call from company HQ (New York) about staff illness in your factory. They have been exploring productivity across the company, and have noticed an apparently high level of holiday related illness in your factory. They present their data on a funnel plot. The data are plotted for all 10 factories and other workers separately.

While the average figure for holiday related illness across the company is 10%, the figure for your factory is closer to 30%. A funnel plot is a quick way to display and assess “variation” in a process (1). The detail of producing and more advanced interpretation of a funnel plot is beyond the scope of this session, but I have provided a simple example that you can adapt to your purposes.

Company HQ asks you to explore and identify ways to reduce staff illness.

As a budding improvement scientist you plan your work using the Model for Improvement. Focusing initially on the first three boxes (we focus on the PDSA part later on):

- The aim you are trying to achieve is to reduce holiday related illness in your factory – you would set a level and date by which you plan to achieve it

- Your measure is staff absence due to illness in the week following vacation – something you already record routinely, but haven’t been looking at systematically

- You work up your change ideas accordingly. Have 3 or 4 ideas you plan to test, to avoid getting stuck down one track.

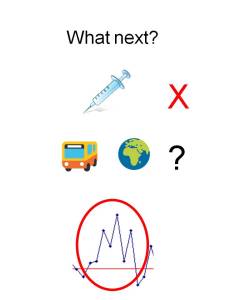

The data in the funnel plot shown earlier are for holiday related illness. You start to think about potential reasons and solutions (change ideas). You know that prevention is better than cure, so start to wonder about setting up a travel vaccination clinic.

In order to plan, and assess the need for a travel vaccination clinic, you decide to ask staff where they are going on their holiday this year (the “hairdresser question”). You can plot this type of “categorical” data quickly on a Pareto chart.

Your initial question, however, does not receive a complete response (purple dots on world map shown). Some people have not yet booked their vacation. You ask them to record where they plan to go on holiday (yellow dots). Finally, some people are going to work right through summer (staycationers recorded with red dots). You have refined your question and operational definition in order to make best use of your data. You can count up the data recorded by your “employees” by keeping a simple tally sheet (eg count by country or continent depending on the type of response you receive).

A Pareto chart allows you to work out where to focus your attention (or prioritise). In this context you are trying to work out whether a travel vaccination clinic is likely to be an effective response to your problem – that of holiday related illness. The Pareto principle states that in many circumstances 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. In this example 80% of people responding to your question are travelling to Europe, within the UK, or the Far East. A little further questioning identifies that none of the destinations require travel vaccination. It appears, therefore, that the planned travel vaccination clinic is not going to tackle your problem. You can score that idea off your list.

A colleague in the Occupational Health team starts to look through the available data (she has data for the whole of 2015).

Rather than look at all the year’s data in one go, she looks at the data over time, plotting the number of employees returning from holiday.

She adds a median. This is a run chart.

She interprets the values using “run chart” rules. There is clear evidence that more employees take holidays over the summer. There are 6 points in a row above the median – this is called a shift. But it’s no surprise that many people go on holiday over the summer.

The Occupational Health doctor digs deeper, however, and adds in further information.

This time she plots the number returning ill from holiday. Again, there is a clear pattern over the summer (another shift). Again, that is perhaps not a surprise because more people are away over the summer.

Instead she plots the data as a % returning ill from holiday. There is another shift over the summer, returning back to the normal level after the holiday period is over. We have adjusted for the fact that more staff are off over the summer period.

Instead she plots the data as a % returning ill from holiday. There is another shift over the summer, returning back to the normal level after the holiday period is over. We have adjusted for the fact that more staff are off over the summer period.

Plotting data over time is often used to monitor progress against an aim. However, in this example it has helped us explore reasons – generate hypotheses using data from the past.

You start to discuss ideas for further testing, focusing on the summer period. The Occupational Health doctor remembers thinking over summer 2015 that there may be a link between mode of transport and staff absence. She looks through the medical records and finds a pretty complete record of travel choices from last summer.

You collect a tally of the data from the medical records.

You collect a tally of the data from the medical records.

You group results by main method of transport.

Plotting the data alphabetically doesn’t help much….

Plotting the data alphabetically doesn’t help much….

…but then you remember about Pareto charts, and plot the data in that way. This shows that 80% of holiday related illness (here classed as infection) related to ferry/ cruise liner, plane or coach trips. Staff take advantage of company perks and travel with the same travel company, often on package tours. There are therefore a limited number of firms with which to work.

Talking to medical colleagues and the staff themselves you start to work up ideas for testing.

Talking to medical colleagues and the staff themselves you start to work up ideas for testing.

There appears to be a link between the summer period and mode of transport. You start thinking about food preparation, hand hygiene and cleaning protocols.

Your ideas for testing focus on keeping food chilled, hand washing, and keeping ill travellers away from other passengers as far as possible. You work with staff and the local travel firm to test ideas. You start now, rather than waiting for the summer. You identify areas for improvement. You chart progress in these areas. By summer time travel firms and holidaymakers are observing good practice around the “4 Cs” (cleaning, cooking, chilling and avoiding cross contamination). Process and outcome measures have improved on your run charts.

In this example we have looked at

- variation (between factories)

- building knowledge (of staff travel and potential causes of illness)

- human factors (eg sloppy habits learnt through the year deteriorate further, and have a particular impact during the warm and busy period over summer)

- a whole system (eg for food preparation)

- plotting data over time in run charts (both to investigate potential areas for testing, and to monitor the impact of testing)

- using other data more systematically (eg through funnel plots and Pareto charts)

The underlined points above are from Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge.

This example (entirely fictional) has been tested with a group of colleagues from a range of backgrounds. It illustrates concepts from quality improvement, particularly around data and measurement, using examples aimed at a general audience. Participants in testing included employees from the health service, local authority and voluntary sector. The group included people new to improvement science and others with extensive experience of quality improvement and patient safety.

Please feel free to use the materials, available on scotpublichealth.com/qualityimprovement, but please credit me if you do (@gmacscotland on Twitter).

Notes:

- The red line in a funnel plot shows the mean value. Figures outside the control limits (dotted lines) are likely to reflect important variation within the system. Your factory (circled) is clearly beyond the upper control limit. This is called “special cause” variation.

Further reading and tools:

QI Hub page on Shewart Control Charts (eg funnel plot)

QI Hub page on Model for Improvement

QI Hub page on Measurement for Improvement (including operational definitions)

NHS Education Scotland Scottish Improvement Skills: How to create a Pareto chart on Excel 2007

NHS Education Scotland Scottish Improvement Skills: How to create a run chart on MS Excel 2007 and 2010

Graham Mackenzie 27 March 2016